Digital Colonialism: Intellectual Property, Global Content Creation and the Politics of Ownership

How the Intellectual Property laws that assign value to content disenfranchises minorities and developing nations due to its inherent bias towards the wealthy, the individual, and the West

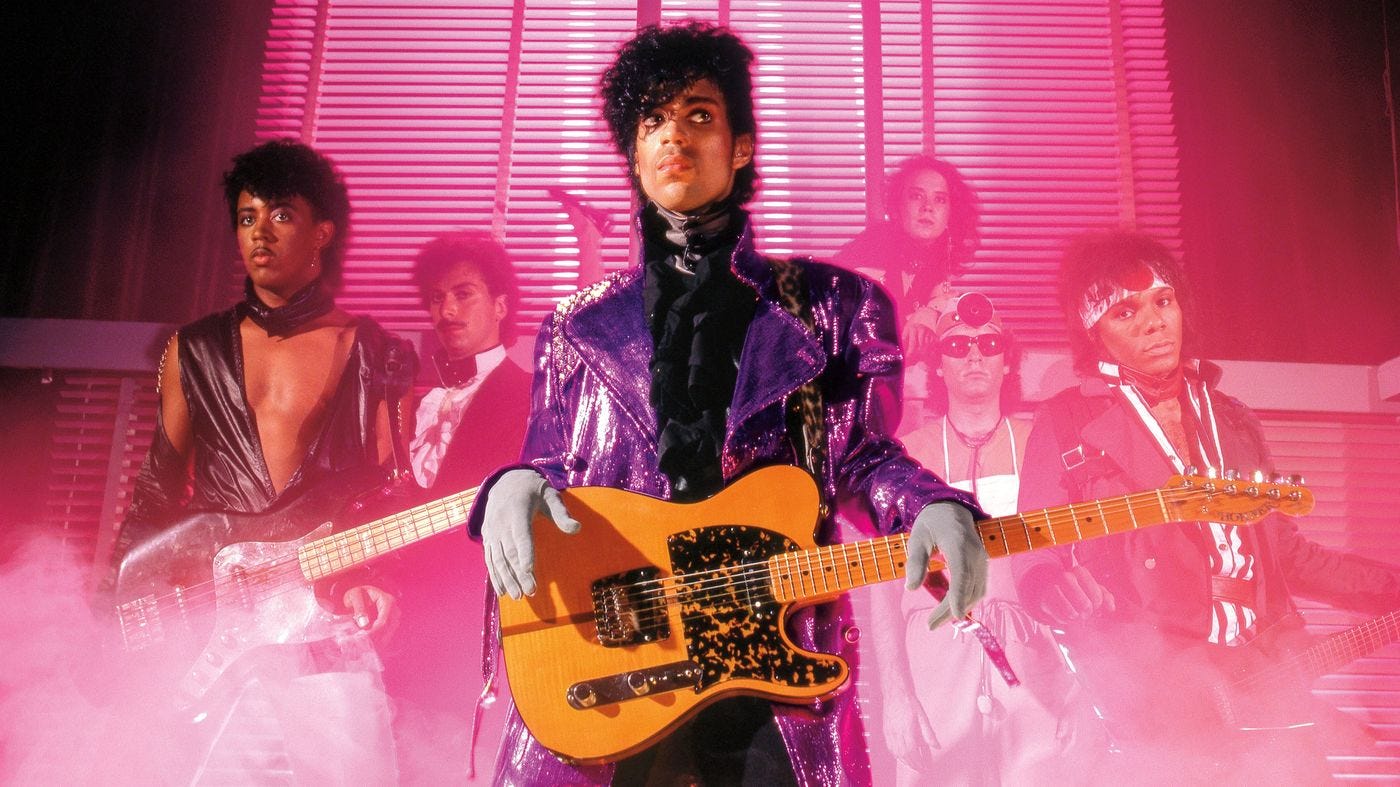

Image: Prince from npr.com

On April 21, 2016, the world woke up to devastating news. Singer, songwriter, and eccentric performer, Prince had passed away. Gone was an incredible artist who did everything his own way. Unswayed by popular culture, he lived a life committed to remarkable authenticity. However, as fans around the world mourned, few knew that a legal maelstrom was brewing that would consume Prince’s estate for the foreseeable future.

By December 2016, the Prince estate would file a lawsuit against RocNation and Tidal, both owned by Jay Z, for including a catalog of 15 unreleased Prince albums to the Tidal database. According to the lawsuit, an agreement had been reached for Tidal to stream one album, namely Hit n Run Phase 1, which had been released earlier in 2015. The inclusion of the 15 other albums was an infringement.

For some, it may have come as a surprise that the late artist’s work was so quickly the subject of a lawsuit, but for those who knew the artist's history, it would seem like business as usual. Prince had a long and consistent role in intellectual property enforcement. A role that began with the career-altering decision to change his name to a graphic symbol to get around music publishing limitations arising from his contract with Warner Brothers. What you don't know is that the artist, formerly known as Prince, couldn’t call himself Prince for his shows, or recordings because Warner Brothers owned the trademark to his name.

Then, as social media platforms evolved with user-generated content, musicians grappled with the unauthorized use of their music online. Prince was relentless at enforcing his copyright. His efforts helped others, setting up legal precedents for fair use in the digital age. For Prince, this was a battle for ownership and control. It was important that he maintained control of the work he brought into the world. Did it make him seem eccentric and a lover of battles? Certainly. But in an age where most creatives are lax with their creative rights, and only pay attention when things go terribly wrong, he had the right idea.

Even still, one has to wonder, with all the effort that the late icon put into protecting his work, and his rights, he still managed to lose his name to a record label for decades. He still had to fight to be given credit and recognition when others created work using his content. What is it about intellectual property laws that make it so difficult to really feel protected? Further, when we examine the global content reach, is this framework equipped to handle the complexities that exist in the developing world, where the culture around creativity and innovation is different from Western regimes?

Image: Madam C J Walker from netflix.com

Rules, Rules and More Rules

Receiving financial benefit is more powerful than having your name on the cover of a book. The economic and creative power over the rights to that book and future direction of the story is crucial. This is a reality that eludes Black creatives. In some ways, public success can become the beginning of professional failures: Hardworking people receiving less and less ownership of their original creative work under the guise of ‘this is how things are done.’

Intellectual Property is a construct built on exclusivity. It’s three pillars—copyright, trademark, and patent—allow an individual or company to exploit their creative work or innovation however they want. These same rights are the owners’ to enforce in the face of the violation, no matter who the violator and no matter the reason. These are powerful constructs that check the free use people may have with certain words, images, phrases, products, and formulas.

Copyrights protect the creative output of authors-- such as music composers, writers, and choreographers. Patents provide legal protection to inventors of useful stuff. Trademark law prohibits the unauthorized use of a valid trademark by others, especially when that usage is likely to cause consumer confusion in the marketplace.

In other countries, there is a fourth right called the Moral right. Moral rights allow creators to preserve their connection to their creative work throughout their life. That means that you cannot see the creative work anywhere without attribution to the original author. Moral rights apply to literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, as well as to films. That being said, the U.S. does not recognize Moral rights.

In the U.S., to own a copyright, patent, or trademark, the creators would seek out an Intellectual Property attorney to file an application on their behalf and submit it to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Now, most people in the Black community have come to associate lawyers with problems. They only go looking for a lawyer when they need help with solving a problem. With more Black people entering entrepreneurship, the reasons for seeking out a lawyer are changing: they may seek out a lawyer to prevent problems unread. For example, a good lawyer would help prepare business formation documents. However, copyright, trademark, and patents are still less likely to bring us to a lawyer’s office.

In fact, the figures that we do have around the Black community and Intellectual Property show that between1970 and 2006, for every million people in the US a Black person would 6 Black people were awarded patents. During the same time period, for every million people, women were awarded 40. In the US overall, 235 patents are awarded for every million people. Another report finds that Black people apply for patents at half the rate of white people, and this is only for patents-- we do not have reliable data on trademarks or copyright applications.

To summarize, Black people aren’t rushing to their attorney to file a patent, let alone copyright or trademark. Now, let’s say that they did want to file for one of the Intellectual Property Rights. And we’re looking for an attorney that would understand their creation. An attorney that would also envision the long term benefit of their patent or business (especially if it comes from their perspective as a Black person). Who would they go to? There are approximately 1.3 million licensed attorneys in the U.S. only 3% of that are Intellectual Property attorneys, and in there, 1.8% are Black, 2.5% are Hispanic or Latino and 0.5% are Native American. Also, 70% of those IP attorneys are male.

Not only do we have an Intellectual Property ownership gap, but we're also challenged with a resource gap. This problem does not only exist in the U.S.--it is a worldwide headache. Some of the greatest minds and thinkers in the Intellectual Property space come from the West. This means that our measurement of efficacy and equity of Intellectual Property will have a perspective bias.

What appears to be a simple concept allowing a creator to maintain ownership becomes a scene riddled with landmines that take out minorities at the intersection of race, gender, and class. Content is rapidly expanding to other nations with varying understanding of Intellectual Property. Some of these abstract rights are poorly understood in these frontiers, leaving creators vulnerable. There’s a potential for another era of cultural looting.

We see the vestiges of it with social media platforms that rake in billions of dollars off the content of creative entertainers all over the world. Creators use their platforms to connect, create, and spread joy. Certainly some build businesses with the audience they amass, but not all avail themselves of the protection of Intellectual Property law. Some will lose much of what they earn because they will not own their content. Many will not own their brands, some will not even own their own names.

Image: Michaela Ceol from indiewire.com

Create 100%, Own 0%

With each headline that celebrates a Black storyteller’s pending deal with a major studio, we often forget to ask about ownership. It is rarely a conversation that comes to the surface, and as a result, it is perhaps a thing creators themselves take for granted until a contract sits in front of them and they are asked to sign. This is why Michaela Coel’s journey to bring her newest project to the small screen is vital for young Black creatives. Something is being lost in translation.

No matter how much representation exists, at the end of the day, long term effects and economic impact will not occur if Black creatives do not own the intellectual property they create in the same way their counterparts do.

In a recent interview with Alex Jung, Michaela Coel discusses her limited series I May Destroy You. The HBO project is an unflinching look at trauma and what it takes to return home to yourself in the wake of sexual assault. Oftentimes uncomfortable, but piercingly accurate and relatable, Coel’s portrayal was necessary, despite the visceral pain of it all.

Ten years ago, I could never have conceived of a story this singular about a dark-skinned, Black woman written, directed, and acted by a young woman of West African lineage. The universe of identity I grew up on was one that played to exceptionalism. The perfect Black family, the perfect Black friends, the perfect Black relationships. The ‘90s were full of sitcoms that spoke to humanizing the good in Blackness, painfully clean and devoid of the darker edges of humanity that exist in all races, nationalities, and countries.

This new generation of writers like Michaela Coel and Issa Rae are crafting a more tenuous truth: young, Black people who are allowed to be vain, arrogant, sloppy, over-sexed, under-appreciated and pissed about it. All while being kind and courteous, loving, and motivated. These depictions of the shadows of humanity wearing Black skin are more relevant and necessary now. Especially at a time when Black Lives Matter is a clarion call for the average suburbanite, and countries around the world are examining the ways in which they ignore, support, or endorse the supremacy of all things ‘White.’

So, after painstakingly building this deeply personal universe, Coel is approached by Netflix and offered a deal to the tune of $1 million. But she turns them down. What is the breaking point? Netflix will not give her any percentage of the copyright. Coel’s singular decision to turn them down is a statement on its own. No, it's not necessarily because Coel is sticking it to the man. This is a far more subtle statement that some may miss entirely.

Black stories have not always been owned by Black people. Commercialized versions of Blackness have been contorted throughout history for the purpose of selling more advertising spots. The focus has always been on creating the right tone for merchandising, the right look for a major sponsorship deal. The images of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Brown, which harken back to a time of Mammies and Uncle Toms, were depictions protected by Intellectual Property and created to appease a racialized society. For a long time, the portrayal of Black humanity was controlled by the people holding the rights and, by extension, the purse strings. Saying ‘No’ to that Netflix deal was rejecting a heritage of disenfranchised Black creatives.

Without ownership, without a seat at the table, the stories we create and deliver to studios and networks can begin walking in a direction we never intended. On the outside, it will appear as a Black story, but the sausage was never meant to have that flavor. That is why saying ‘No’ mattered.

Even though Netflix has generally been a force for good in many countries, it doesn’t matter-- that isn’t the point. Netflix can still be a benevolent savior and we would still have a system that divests its creators of their Intellectual Property. This new world of digital content creation and distribution is full of untested rules. It demands that we examine the ways in which intellectual property laws interact with cultures far more complex and ancient than the technologies of our modern day.

Image: Teff plants from qz.com

Individual Wealth vs. Collective Value

The challenge of protecting your content as an individual creator is common. Regular people do not understand Intellectual Property laws, even though they interact with these laws every day. The only way to really protect yourself comes down to knowing that you have something worth guarding and finding the best possible legal professional to guide you along that journey. But what happens if you are an entire country or ethnic group?

Traditional knowledge is a kind of innovation that complicates global conversation around Intellectual Property. It pushes the complexities of communal ownership vs. individual ownership forward. More specifically, who gets to own various facets of culture? And once owned, how do you control it?

First, it is important to define what counts as Traditional Knowledge. In her article Intellectual Property at the Intersection of Race and Gender, K.J. Green defines it as ‘indigenous and local community knowledge, innovations, and practices, often collectively owned and transmitted orally from generation to generation.’

This kind of knowledge has an emphasis on the community, both in the ownership and exploitation, that it does not fit neatly within the paradigms of Intellectual Property law as it exists. Not only that, but some of this knowledge is also so old that it may be considered part of the public domain, thereby stripping it of value. Regardless of whether it sits as the foundation for other innovations or creative works.

A Dutch company, Ancientgrain, filed a patent for teff related products in 2003. This process of turning teff grain into flour and then making bread from the flour was created by senior company official Jans Roosjen, according to Ancientgrain claims. The problem is that Eritreans and Ethiopians have been using teff for millennia to make their national spongy bread, injera. So effectively, Ancientgrain was claiming that they had invented how to turn teff into a flour even though an ancient culture had been doing it, literally, forever. Somehow the patents were issued despite outrage from Ethiopians. In fact, the Ethiopian ambassador to the U.S., Fitsum Arega, stated that this patent prohibited Ethiopians from exploring a growing global market for the grain, which some are touting as a superfood.

Then in 2014, another Dutch company, Bakels, created a teff-flour mix that Ancientgrain claimed infringed on their patent. Ancientgrain then filed a lawsuit in the Netherlands. Bakels’ argument was that the process for creating the flour for baked goods lacked inventiveness. A year later the Netherlands’ Patents Office backed Bakels’ argument and found the patent invalid. The case went all the way to The Hague and there it was determined in 2018 that the patent did in fact ‘lack inventiveness’ and was therefore invalid.

Here is the problem: while the patent is invalid in the Netherlands, Ancientgrain received patents in Australia, Italy, and other countries. Clearly, the intention was to take a grain that was integral to Ethiopian culture and own exclusive rights to its production into flour and exclude the indigenous community and, quite honestly, anyone else from benefiting from that innovation.

Though it seems like a victory at the Hague, there is a secondary problem here: if Ethiopia or an Ethiopian representative company tries to patent teff-related products, wouldn’t it still be invalid because the process lacks inventiveness? So how, then, can this country and its people capitalize on their discovery and creation of injera bread? Since this is a relatively new case and the issue has not been entirely resolved globally, it is worth keeping an eye on.

In a different dispute, the Walt Disney Company, which has had its brushes with global content and appropriation, came under serious fire because of an old trademark. In 1994 when the animated version of the Lion King came out, Disney trademarked the swahili phrase ‘Hakuna Matata.’ Swahili, a language spoken by a large swatch of people living on the continent of Africa, has had this phrase since time in memorium. Obviously, it came as a surprise to many people that Disney would trademark the phrase of a widely spoken language.

However, this is where confusion around Intellectual Property comes in-- the trademark for ‘Hakuna Matata’ is limited to merchandise, which would allow Disney to sell products that have the branding associated with the film. So, even though the phrase was indeed trademarked, the use and exclusivity was limited only to Disney’s film and its use of the phrase within the film.

Limited use of Intellectual Property like Disney’s, is in stark contrast to the wide claim to ownership Ancientgrain asserted over teff. Some may say that is more acceptable. Others may still cringe at a foreign corporation’s ability to copyright a phrase from another language for commercial use, no matter how limited. Who gets to decide when copyrighted, trademarked or patented works derived from another country or culture is ok? What is the threshold for the discussion and who gets the final say?

Image: Kenyan men from cnn.com

Where the Rubber hits the Road

There is a dangerous economic disparity caused by our current Intellectual Property frameworks. For cultures that use oral tradition to pass down their histories, who use stories as a means to educate, to train, and learn about the world around them, art and creativity do not feel like commercial elements. Perhaps it is the historically communal nature of these creative works that make it difficult to fully accept an individual’s claim on the value. Meaning, when stories have belonged to the collective for so long, why must we now pay the person who took the time to write it down?

In examining the countries that struggle the most with Intellectual Property compliance, is it coincidental that there is a strong communal history that still impacts the day-to-day lives of those people? Is it an accident that most of those nations also share a legacy of colonialism which has confused some values and restructured society in incalculable ways? Is it by chance that these same people are routinely creating content at a pace that is astonishing, but unable to realize the economic value? Perhaps not.

So, since we cannot go back in time to right old wrongs, and cannot hit pause on the present rapid globalization, what, then, must be done about the creative nations who are leaking economic value? How can Intellectual Property become a force for good that brings about economic improvement in communities around the world? Ownership. There must be a radical expectation that creatives own their content, at the highest possible level, and resist the desire to use business-legal reasons to erase those voices.

Without the credit, without the ownership, there is nothing. The content business has run a particular way for a long time and the balance of power has been as it is for, perhaps, even longer. Now, as we extend ourselves into new territories with different understandings of ownership and control, the industry cannot expect creatives to live off the flashing lights. A real conversation about the complexities of creativity needs to be had. At the end of the day, content is not just for entertainment. It has been proven to be a real source of economic empowerment in developing nations, and there is only so long that creatives will agree to eat cake.

The Content Biz Bailout

Data is a big part of the Intellectual Property debate largely because the value of Intellectual Property has a lot to do with who is interacting with particular content, how frequently, and at what level of engagement. This article discusses how data is an asset of the Digital economy and some thoughts on what global data rights might look like.

This piece utilizes Critical Race Theory to deconstruct the racial history of Intellectual Property Law in the U.S. and asks what an equitable framework for creative ownership would look like if it took into account all people.

The American Bar Association (ABA) in 2017 found that less than 3% of all attorneys are Intellectual Property attorneys, and of that, 1.8% of those IP attorneys are Black. Read the rest of the report by the ABA on the lack of Black IP attorneys and why it’s a problem.

The streamers will have a significant role to play in attribution and the discussion around content ownership because they are playing a global game. That being said, it is important to think about how they will be changing the nature of Talent Agreements. This piece by Ken Ziffren examines this changing dynamic and gives us all something to think about as we look to the future of global content.

Congress convened a subcommittee in 2019 to address the diversity gap in patents. There is a recognition that untapped potential and economic power exist in underrepresented communities and there is a need to unlock that potential. This holds the nation back and therefore, there is a need to examine where the issues arise. Here is the report from that committee.

Does anything about this change when you create in the tech space, such as apps and software?